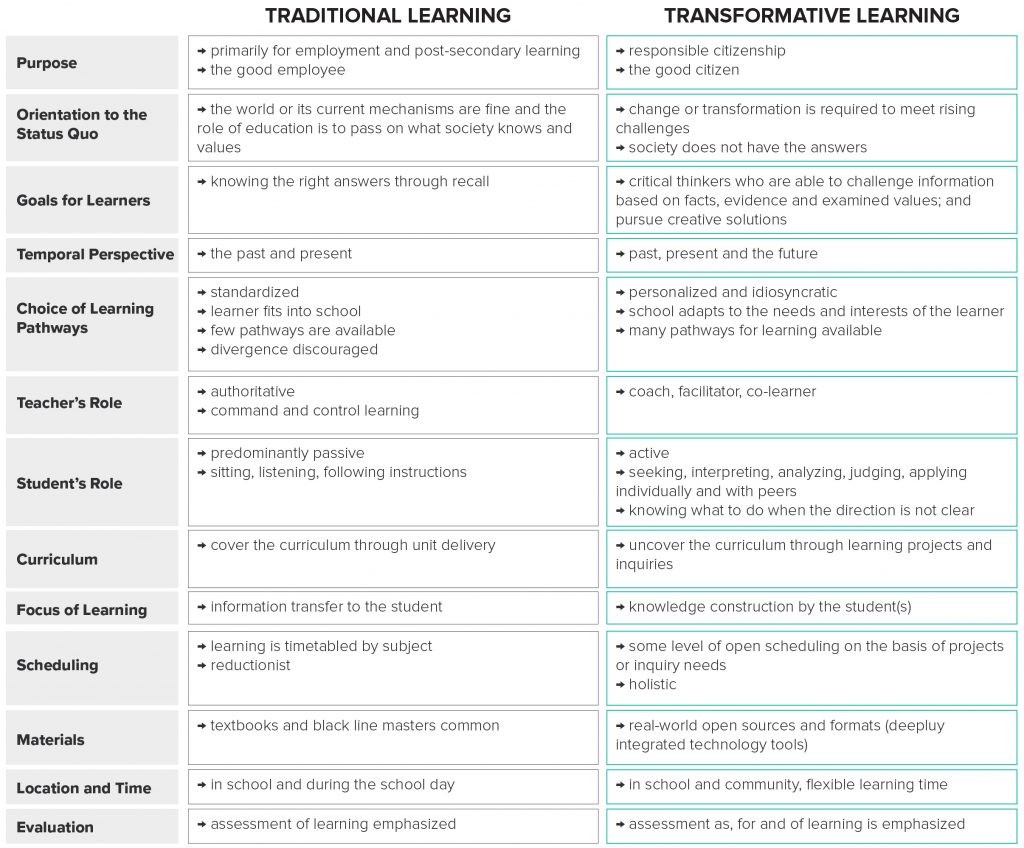

Transformative learning happens when schools shift the focus from a paradigm that emphasizes knowledge acquisition to a one that has a focus on the factors that tap into a student’s potential toward affecting their community in a positive way. This perspective teaches students that they can ask questions, develop their skills and knowledge alongside their teachers and to learn to solve problems. Notice the difference between conventional and transformative learning experiences.

Transformative learning develops engaged, responsible citizens who learn individually and collectively.

Kozak & Elliott, 2014

This chart is a useful tool in comparing traditional and transformative learning practices. Adapted from Miller, 1988.

The Role of the Teacher

The role of the teacher is changing to support the transformative learning experience, which includes inquiry and experiential learning opportunities. Teachers now act as mentors, co-learners and coaches, providing guidance and modeling learning throughout the process. They can learn and work alongside students to frame thoughtful questions, explore new ideas and plan and develop meaningful tasks.

To be effective, teachers should foster a sense of respect and trust between members of the group. They should be process-oriented, model flexibility and be able and willing to adjust to unforeseen obstacles while identifying the learning in the process. Teachers work with students to identify timelines, debrief and reflect upon learning experiences and define a project scope as needed to ensure success. Like the students, the teacher should reflect on how things are going and how they could be improved.

Bold School (Jagdeo and Jensen, 2016) discusses three types of teaching styles that facilitate inquiry based learning and community classrooms.

Mentoring “Be an observer”

Teachers observe the verbal and non-verbal communication in a classroom, and look for ways to engage in individual curiosity. Moving from group to group, the teacher facilitates questions and probes students to think, look for knowledge and create solutions to problems. From these observations teachers can further design exploratory moments.

Co-learning “Partner with and alongside students”

Teachers should model the learning process by demonstrating that they have questions too. By engaging students in planning tasks and research that is normally done solely by teachers, students become insiders and own decisions in the learning process.

All community members are able to share their strengths, bring something to the table and are valued in the co-learning model.

Coach “Provide feedback and personalize learning”

Teachers provide specific, ongoing, timely and descriptive feedback to students. Acting as a coach also develops trust and strong relationships between the teacher and student. This can lead to further feedback in all areas of life, creating a holistic understanding of what makes each student’s learning journey unique.

Experiential Projects

Students today must now learn how to learn while responding to endlessly changing technologies and global conditions. Experiential learning – learning by doing – engages students in understanding what they would like to learn, how to achieve their goals, and has long-lasting impact on the student. This can be applied to any

kind of learning through experience and engages students in a structured learning sequence, which is guided by a cyclical model of the learning cycle.

Teachers are increasingly recognizing experiential pathways,

such as project-based learning, as a means to benefit the learner while also having a positive impact on the community. Experiential project-based learning has been touted as one of the most effective teaching frameworks that demonstrates students learn more deeply and have better understanding if they are involved. This involvement has the most impact on student achievement, more than any other variable, including student background and prior knowledge (Barron, 2008).

Experiential projects increase students’ abilities to think critically and creatively, plan projects and define problems with clear arguments, as well as capacity to improve motivation, attitudes towards learning and work habits (Barron, 2008). This type of learning has a focus on real-world problems that capture students’ interest and excitement and has proven to increase later engagement in similar ventures (Efstratia, 2014).

The emphasis on collaboration common in experiential projects has also shown to have widespread benefits. Hundreds of studies have been conducted on cooperative learning and have all arrived at the same conclusion —there are significant advantages to working with others on learning activities. When solving problems, teams outperform individuals and individuals who work in groups tend to do better on individual assignments. Beyond academic achievement, research also shows that cooperative group work improves individuals’ interpersonal skills (Barron, 2008).

In the face of worsening problems in our society and environment, we must be active observers and engaged in our communities. Solutions for community problems cannot be found in a textbook. Instead, students, teachers and community members must seek answers by asking essential questions and through active engagement. In addition to preparing the next generation to find solutions to considerable economic, social and environmental issues, schools are an ideal community resource, where students are active participants in community initiatives. Experiential projects provide students with the opportunity to play a meaningful role in their community.

Although it is clear that experiential projects have numerous benefits to both the community and the learner, research has also shown that educators find them difficult to implement, limiting their effectiveness (Hutchinson, 2015). Educators commonly misunderstand experiential projects as being unstructured and ‘hands-off.’ This approach often leads to unproductive learning experiences, where students lack the necessary support and assessment as the project develops (Barron, 2008). Furthermore, the change in responsibilities brought by an experiential project learning presents teachers with new challenges, such as project management, facilitating collaborative learning, community outreach, developing assessments to help guide the learning process and illuminating key concepts in a multidisciplinary learning experience (Barron, 2008). To overcome these challenges, teachers must embrace their shifting role to mentor, co-learner and coach.

Collaboration

Collaboration is a critical element in experiential projects. Students work as a team by recognizing, appreciating and building off and onto each other’s unique strengths to reach a common goal. This is done by first establishing a sense of community in which all members are considered equals and have a place to speak and to be listened to. In the first module of the program, students engage in various community-building activities, where they become familiar and comfortable with each other. Bonds and deeper understanding between people are created. Throughout the module, dialogue

is facilitated and ideas are shared and explored in a open and welcoming forum. This method of conversation is essential to making sure all members feel heard and can play an equal role in the collaborative process of community building and experiential projects for entrepreneurship and career development.

Observation, Inquiry and Community immersion

It is essential that students are aware of the community’s needs, available resources, and its challenges. The first step in gaining this information is when the local community is observed and explored. After data is collected students can choose an area of interest for career development through an experience: job shadowing, attending local events and entrepreneurial activities. Students should frequently engage with their community, seeking local expertise and knowledge. Students can then define what it is they would like to study and define an experiential project which will require ongoing maintenance. Students should work with the local community to ensure the entrepreneurial project’s continuation, post-program.

Experiential projects are immersive. Students should learn and work together on individual and group projects in many learning environments, that directly offer hands-on experience, skill development and knowledge connected to their learning goals. It is important to recognize that because of the nature of time, days must be properly planned and organized. The use of time is essential in building experiential programs that have long lasting and meaningful connections to community.

Although experiential projects can be modified to work within the confines of more restrictive schedules, it is most effective when timetables allow for longer periods of study so immersion is possible. When planning community and entrepreneurial experiences, it is important to take this aspect into consideration. Work with your community, school leaders and students to consider what timeline will be most effective for this course.

Systems Thinking

How do we look at the world? Systems thinking means looking at the big picture, examining the connections, relationships and interactions between everything around us. Systems thinking is valuable for many reasons. When actions affect the environment or visa versa, we must think in systems to find solutions. For example, the use of DDT as a pesticide had positive short term effects but caused long term negative effects on our health and the health of ecosystems. Taking a systems thinking approach helps us understand the complicated nature of the obstacles that challenge us and makes learning ideal when it has a focus on real life situations that are emergent and authentic.

Characteristics of Systems

- The parts of a system are interdependent and connected

- Patterns and structure of the connections determine how the system works

- System behaviour is emergent and unpredictable

- Feedback loops control a system’s dynamic behaviour

- The parts of systems are cyclical not linear

- Systems are complex, diverse and unpredictable

Adapted from thwink.org/sustain/glossary/SystemsThinking.htm

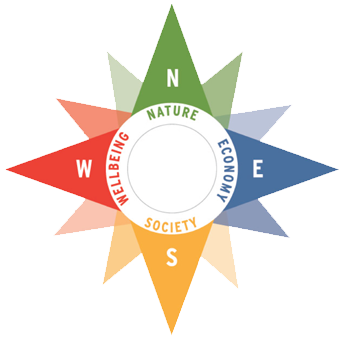

An important tool we can use to develop systems thinking is viewing things through a sustainability lens. This tool is helpful while observing a community and its complex interactions. The specific areas of focus using this tool are: environment, society, culture, and economy. Compass Education proposes the Sustainability Compass:

Compass is a methodology for orienting people to sustainability. Compass helps you bring people together around a common understanding of sustainability, and a shared vision for getting there. It also helps you monitor progress along the way. First developper in 1997, the Sustainability Compass has been used by companies, communities, organisations, schools and universities around the world.

The Sustainability Compass is easy to understand. A regular compass helps us map the territory and find our direction. This Compass does the same thing for sustainability. It takes the English-language directions (Norht, East, South, West) and renames them while keeping the same well-known first letters:

- N is for Nature. All of our natural ecological systems and environmental concerns, from ecosystem health and nature conservation, to resource use and waster.

- E is for Economy. The human systems that convert nature’s resources into food, shelter, ideas, technologies, industries, services, money and jobs.

- S is for Society. The institutions, organisations, cultures, norms, and social conditions that make up our collective life as human beings.

- W is for Wellbeing. Our individual health, happiness, and quality of life.

From compasseducation.org

Teachers and students can use this tool to guide observation and inquiry around any topic by exploring the four different aspects of sustainability. This does the following:

- It adopts a systems approach.

- It promotes divergent thinking and questioning.

- It encourages learners to ponder issues from the perspective of others, analyze the relationship between them and recognize thecomplexity of fulfilling the needs of all creatures on earth.

Differentiating

Differentiation is when teachers use different ways to deliver lessons, review material and check for understanding. It is an approach that responds to the individual needs of students. In most situations, students who experience a differentiated practice can access many pathways to learning. Differentiation takes into account the whole person’s personality, strengths, abilities, challenges and past experiences, while considering that different individuals need to experience lessons in different ways. Areas to differentiate include the content, process, product and environment of learning.

Content

Teachers may adapt what they want students to learn. All students are working towards the same skills or standards and objectives, but will achieve them in different ways. Tips include the following:

- Use different texts, novels or short stories at a reading level appropriate for each individual student

- Use flexible groupings based on the content, interests or skill set, reading ability or have students assigned to like groups listening to audiobooks or accessing specific internet sources.

- Have a choice to work in pairs, groups or individually

Process

Teachers may be flexible about the process of how the material in a lesson is learned. This includes using a holistic model that encourages different ways to obtain information.

Assessment Tasks

Teachers may adapt what the student produces at the end of the lesson: tests, evaluations, projects, reports and other activities. Based on a student’s unique self, teachers can be creative with the way they demonstrate their understanding of a topic. This could be a written report, composing a model or writing a song, but should build upon the process they have used to understand and experience the topic.

Learning Environment

Teachers must consider the learning environment and general atmosphere, depending on the needs of the group. This can include thinking about the use of space, light and walls. The learning space should be arranged with areas for quiet individual work, as well as areas for collaboration and the whole group, but is not limited to the classroom. It should create a safe and positive atmosphere while allowing for a dynamic and flexible approach to learning.

Feedback

Feedback happens when educators or students give up-to-date information & observations about the effects of a student’s actions while trying to reach a goal. It is not advice, a value judgement, or recommendations on what should be done differently. It is a retelling of the student did and what the outcome was. It often leads a student to ask the question, “What can I do next to improve and to achieve my goal”?

Feedback is the most common way to tell if a learner is growing or developing from an experience. It is a great way to transform an individual’s learning moments into success – more so than the use of grades, testing and other static forms of assessment. In most cases, feedback is a verbal or written piece that includes the following sequence:

1 What? – 2 So What? – 3 Now what?

In other words:

- What was the goal and what did you do?

- What was the effect of your actions and where are you at in relation to the goal?

- What can you do next to reach the goal?

There are various tools for engaging in feedback which include the following:

- Reflection

- One-on-one conferences and conversations

- Checklists

- Verbal feedback

- Rubrics

Feedback should be linked directly to the achievement of the Competency and Critical Skills. In the appendix you will find the criteria for the Inspire Nunavik Critical Skills and teacher prompts.

Debriefs

Debriefing is a form of feedback that looks like a question and answer session with participants after an activity or experience. These are activities that engage students in articulating, exploring and connecting their experience to their personal skills, others and real world situations. Debriefing takes teachable moments and unpacks them for the

details of what happened, and why it matters and what could be done differently next time. Debriefs also involve the feedback sequence discussed above (What? So what? Now what?)

During the debrief, students can recognize their skills and strengths

by naming them, and being aware of them in the future. This practice allows the learner to develops a deep, accurate and intuitive understanding of themself. Debriefs can happen early in the experience, in the middle, at the end, or even as a periodic check-in to stay on track. Most important is to make sure that they are planned and if they are not planned that they have a purpose in mind. Here are some reasons to debrief an experience:

- to reconvene a group for routine

- to build classroom community

- to reset the tone and expectations of an activity for safety

- to review the objectives for expectations and assessment

- to give feedback for personal growth

- to recap learning to determine outcomes

There are many different activities and tools you can use to organise and lead a debrief. Here are some recommended resources:

Reflections

In this course, students are expected to continually reflect on what they are doing, why it matters and how it could be improved. This can be carried out in a number of ways. For example, pair shares, group shares, reflective writing and journals or question-and-answer and debrief sessions.

Journals

Reflective practice for learners starts with the process of keeping a journal. Students often respond well when journals are presented as a way for them to document the details of their learning experience and what they are finding the most enjoyable or least enjoyable in the day. Journals can be kept anywhere, are portable, and can be unique to everyone. The journalling process can be formalized as an activity to capture the end of an experience and steps for the next day or they can be used as a reference for weekly feedback, check ins and assessments.

You can certainly make this cycle more challenging & meaningful by teasing out the reflection and using Gibbs Cycle:

- Description – What happened?

- Feelings – What did you think and feel about it?

- Evaluation – What were the positives and negatives?

- Analysis – What sense can you make of it?

- Conclusion – What else could you have done?

- Action Plan – What will you do next time?

- Feedback and Follow Up – What advice do you have for the learner and how will you follow up?

Your students should all have a journal in which they regularly take notes about aspects of their learning and life experiences. They can use the journal as a resource for collecting ideas and responses to activities and topics. Once journals have become regular practice, use some or all of Gibbs model to hone in on specific parts of the practice that you want the learner to develop.

Teacher Journals

Taking the time to reflect on your work as an educator can help you

find meaning in your work. This is an important practice since it will also help students develop meaning about their work. Reflective practice can become an important part of documenting and communicating the value of your program or course offerings. By engaging in journaling you can synthesize the “story” of your teaching, including your successes and failures. Keeping a record of what happens in your work can capture those “on the fly” moments of spontaneous creativity when you need to rescue a situation or make activities better. Keep track of what worked, why it worked and why it was important.

Carve out time in your schedule to record and reflect on experiences and process and to record observations about student engagement and progress. When you regularly reflect specifically on your work and its meaning, methods and outcomes, you will continually improve by looking deeply into the WHY behind what you do. Furthermore, having this on hand when you look at a student’s reflections, you can have a better sense of the appropriate feedback to provide.

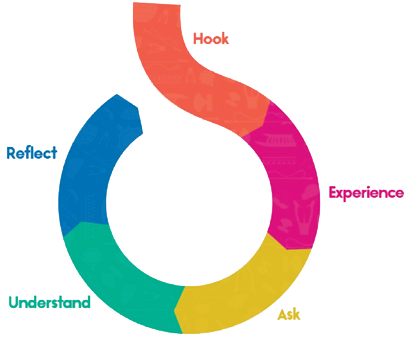

Learning Cycles

Learning cycles are an important tool in creating a culture of engagement and grounding experiential learning. The learning cycle

is a means of representing sequences of activities to connect all of the pieces with experiential learning. In this metaphorical loop, students are inspired to ask questions, dig deeper to find answers, reflect, and see where their new knowledge fits in real contexts. Learning cycles are a dynamic way to structure classes and modules around experiences. It helps to ensure students are observing and following a process that will lead to meaningful feedback and further learning.

It is often assumed the stages of a learning cycle are managed by a teacher, but they can also be self-managed, or, in high-functioning learning groups, unmanaged. In this way, learning from experience becomes an intuitive, everyday process. The learning cycle can follow many models, but we suggest using – Hook, Experience, Ask, Understand, Reflect.

Learning cycles can be modelled using visual aids, such as the one below:

- Hook – What short activity or provocation will engage learners?

- Experience – What community activity will learners observe or immerse in?

- Ask – Debrief with learners to understand more about the experience and ask questions about what else is to be learned

- Understand – Research, collect and synthesize to understand what the experience meant and to answer questions

- Reflect – Journal, give feedback, debrief again

- Experience – What experience is next? Look for opportunities of further investigation or new experiential learning